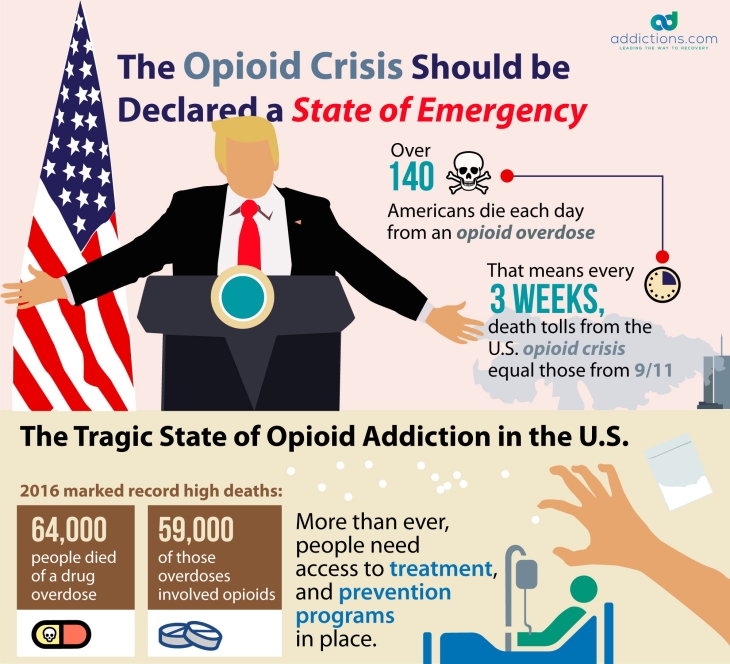

Every day, more than 140 people in the U.S. die from an opioid overdose. This means that every three weeks, America suffers a death toll equal to that caused by September 11th. The U.S. remains in the midst of a serious opioid epidemic that continues to worsen every year, and that caused over 59,000 deaths in 2016 alone.

In an effort to curb opioid overdoses and deaths around the country, President Trump recently declared the opioid epidemic a public health emergency. This declaration is backed by promises made by the Trump administration to increase access to opioid addiction treatments, accelerate the hiring process for opioid experts who can help with the crisis, and supply grants to those who have trouble finding work on behalf of opioid addiction.

Though the Trump Administration may have good intentions behind declaring the opioid crisis a public health emergency, many Americans feel that more should be done to curb the problem — such as declaring the opioid epidemic a national emergency rather than a public health emergency.

What’s the difference between a public health emergency and a state of emergency, and how can a declaration of one or the other help with the opioid epidemic? Here’s a closer look at the current state of the opioid epidemic, and how a state of emergency could potentially save the lives of thousands of Americans and improve public safety across U.S. communities.

Current State of the U.S. Opioid Epidemic

Drug overdoses are now the leading cause of death of Americans under the age of 50 — most of which are being caused by heroin and painkillers. America’s drug overdose death rate rose by nearly 20 percent from 2015 to 2016, and is projected to rise even higher by the end of 2017. The opioid epidemic has even lowered the average U.S. life expectancy to only 78.8 years — the lowest it’s been since 1993 when HIV and AIDS were contributing to thousands of deaths nationwide.

Though opioids have been used to treat pain for many decades, the drugs became more widely available during the 1990s when pharmaceutical companies began to aggressively marketing opioids to both physicians and consumers. After the mid-1990s, opioid use rose gradually from year to year, and is now at an all-time high, along with overdose deaths. In 2016, heroin use reached an alarming 20-year high, with heroin-related deaths having increased five-fold since 2000.

Heroin is the most addictive drug in the entire world, and is often easier to obtain, lower in cost, and higher in potency than most prescription painkillers. Since heroin is also an opioid, Americans who struggle with painkiller addiction often head to the streets to buy heroin when painkillers are no longer cost-effective or easy to obtain. Heroin can sometimes trigger an overdose after just one use — especially when the drug is mixed or cut with cheaper, stronger, synthetic opioids like fentanyl and carfentanil.

Declaring the opioid epidemic a public health emergency can certainly help many Americans overcome addiction. However, more help may be needed on a larger scale to drastically reduce overdose death rates across the entire U.S.

What’s a Public Health Emergency?

A public health emergency, which is declared through the Public Health Services Act, addresses a disease or disorder that threatens the general public, and that can bring sickness to large populations quickly and unexpectedly. A public health emergency can happen at any time, and can either occur naturally or be man-made.

Examples of public health emergencies include the spreading of new, unusual, or rare diseases such as Ebola or Zika, mass fatality accidents, and severe weather emergencies. Public health emergencies may also include environmental and social problems such as gas leaks, chemical spills, and opioid overdoses that occur on behalf of addiction.

Under a public health emergency, extra resources are released to resolve the health crisis, and certain health-related mandates are often waived to improve the emergency. For example, now that the opioid crisis has been declared a public health emergency, Medicare patients who struggle with opioid addiction may be allowed to seek addiction treatment from out-of-network providers at no extra cost.

What’s a State of Emergency?

A national state of emergency, which is declared through the Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act, is roughly defined as a situation beyond the ordinary that threatens the safety and lives of American citizens, and that cannot be resolved with current laws and existing resources. A national emergency allows the President to call on federal assistance from a number of departments that can collectively address serious and short-term national crises.

Many times, a state of emergency is declared to help the country recover from natural disasters, such as the damage caused by hurricanes. If a state of emergency were declared for the opioid epidemic, funds that would usually be allocated for natural disasters would be applied toward curbing overdose deaths.

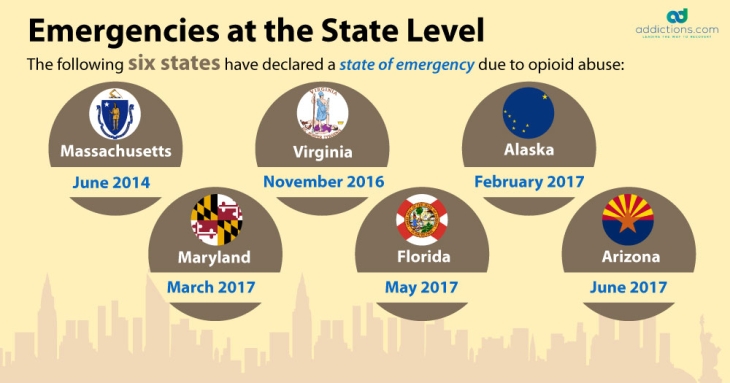

There are 28 active states of emergency in the U.S. — the oldest of which dates back to 1974, under Jimmy Carter’s presidency. The first-ever state of emergency was declared at that time during the Iran hostage crisis, and blocks any Iranian government property from entering the U.S.

Many of the 28 active national emergencies involve the blocking and prohibition of transactions with terrorists and countries that pose potential threats to the U.S. At present, there are no active national emergencies directly related to diseases and health such as the opioid epidemic.

Public Health Emergency Vs. State of Emergency: What’s the Difference?

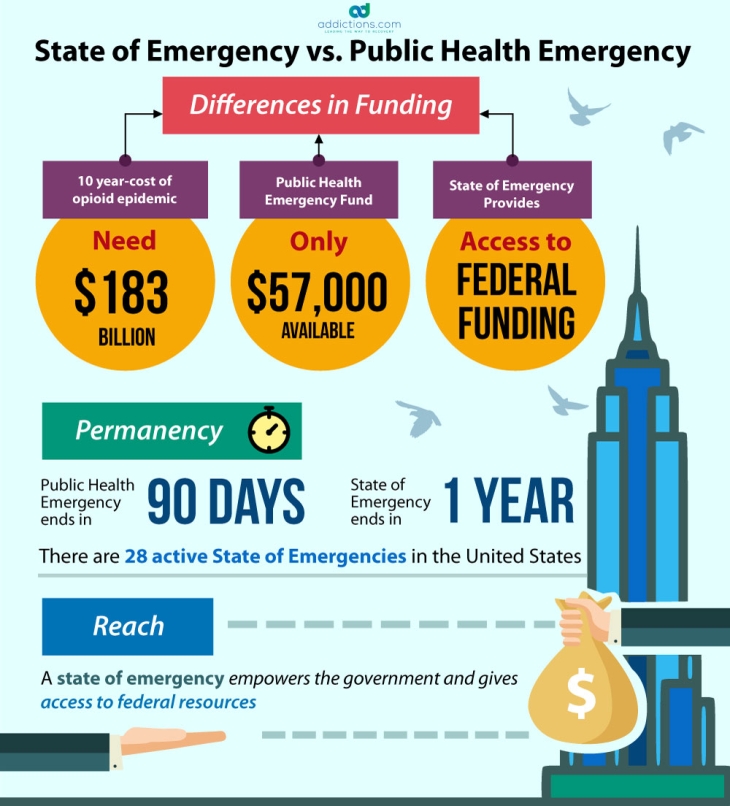

Public health emergencies expire after 90 days, while national emergencies expire after one year. Both types of emergencies can be immediately renewed by the President upon expiration. Many in favor of declaring a state of emergency say that a longer policy life is more effective at addressing a crisis that requires long-term plans and solutions.

Other main differences between a public health emergency and a state of emergency include the source of the funding, and the manner in which each emergency is handled by their respective departments. For instance, under a public health emergency, federal health officials can waive certain patient safety and privacy regulations, and modify requirements pertaining to Medicaid, Medicare, and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Funding can even be used to create temporary healthcare positions for the treatment of said health epidemic.

But declaring the opioid epidemic a national state of emergency could result in having the crisis resolved both financially and logistically by a number of federal departments with the common goal of fighting opioid addiction. For instance, a state of emergency could result in funds being allocated toward helping federal law enforcement tighten security at U.S. borders and reduce trafficking of heroin and illicit painkillers.

How Could a State of Emergency Fight the Opioid Epidemic?

If the opioid epidemic were declared a state of national emergency, the federal government could apply a higher amount of resources and money toward helping states that suffer the highest opioid overdose death rates. Ohio, Kentucky, and West Virginia are just some states that could benefit from increased funding for addiction treatment, addiction education, and opioid overdose antidotes.

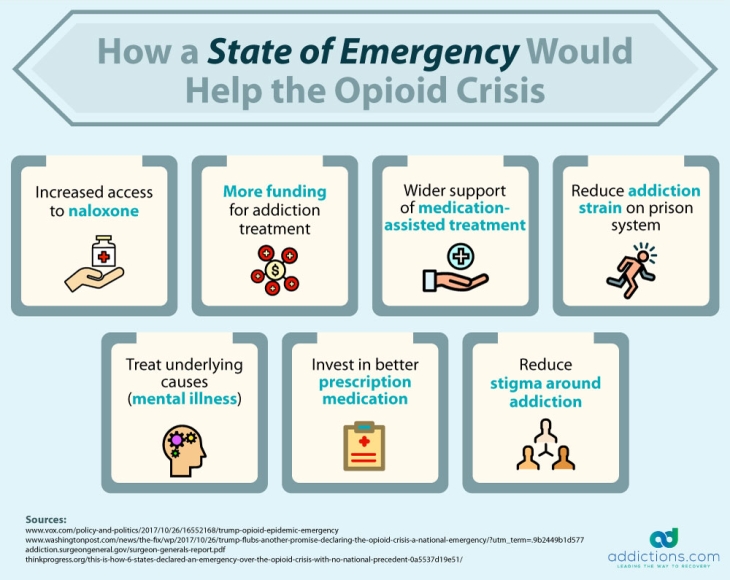

Here are ways a state of emergency could benefit the U.S. opioid crisis.

Increased Access to Naloxone

Naloxone is an opioid overdose reversal drug that blocks the effects of opioids and reverses an overdose while it’s happening. A state of emergency would increase access to naloxone for first responders and family members of those who suffer from opioid addiction. This would involve making naloxone available without a prescription, and increasing supply nationwide.

Removing the Stigma from Addiction

Many states “punish” drug users by sending them to jail instead of offering opioid addiction treatment. A state of emergency could allow for all states to connect non-violent drug offenders with addiction treatment, and remove the stigma surrounding addiction. This would also help the country save billions on costs normally spent on incarceration.

More Funding for Addiction Treatment

Thousands of Americans who suffer from opioid addiction fail to seek treatment on behalf of financial problems. But a national emergency could result in more affordable treatment options, as well as grants that can be awarded to qualifying patients.

Wider Support of Medication-Assisted Treatment

Opioid addiction is commonly treated using medications that allow patients to safely, comfortably, and gradually overcome opioid dependency without suffering dangerous and severe withdrawal symptoms. But some view medication-assisted treatment, or MAT, as a way to replace one addiction with another. Declaring a state of emergency could result in wider acceptance of MAT by requiring that physicians in federal healthcare settings use these medications to treat opioid addiction.

Opioid Addiction is a Public Health Emergency: What Happens Next?

Many Americans and policymakers are in favor of declaring a state of emergency for the opioid epidemic, but some officials are saying that a public health emergency is sufficient enough to handle the crisis — especially given the U.S. was recently been affected by three major hurricanes that exhausted national emergency funds. Calling a state of emergency could put excess burden on the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Disaster Relief Fund, which is used primarily for those types of emergencies.

Additionally, many say that the opioid crisis is too complicated to be resolved by a national emergency, and that public health officials are better equipped to handle the opioid epidemic as a public health emergency.

Here’s how the Trump Administration proposes to address the opioid epidemic as a public health emergency:

- Offer telemedicine in isolated areas. Patients who live in rural or isolated areas and who cannot physically visit doctors may be able to receive opioid addiction treatment using telemedicine.

- Speed up the hiring process of healthcare officials. The Department of Health and Human Services plans on accelerating the hiring process so there are more healthcare workers to address the opioid crisis.

- Offer grants to workers with opioid addiction. The Department of Labor may offer a higher number of grants to workers being directly affected by opioid addiction, and who struggle with finding employment on behalf of their addiction.

Opioid Addiction Treatment

The number of Americans who suffer from opioid addiction has risen by 493 percent from 2010 to 2016. However, only a small percentage of these individuals are receiving treatment, while the rest remain at high risk for suffering an overdose. Fortunately, those who need help fighting opioid addiction have a number of options when it comes to treatment.

Opioid addiction is most commonly treated in an inpatient rehab setting. Since opioids are among the most highly addictive drugs in the world, intensive care is often required to ensure patients can safely withdraw from these substances with a lowered risk for serious side effects. With inpatient rehab, patients can live at the facility for the duration of treatment, and be monitored around the clock by medical staff who can intervene at any time to relieve withdrawal symptoms.

Detox, therapy, and aftercare are the three most important components of opioid addiction treatment. Detox helps patients overcome physical dependency on heroin and painkillers, while therapy in the form of counseling and support groups help patients overcome mental and psychological addiction. Aftercare programs take place following treatment, and help patients stay on track with sobriety and good overall health after having fought addiction.

Those afraid to seek addiction treatment for fear of suffering painful and severe withdrawal symptoms have the option to undergo MAT — a therapy involving the use of medications like methadone and buprenorphine that relieve symptoms. MAT can be used in an inpatient or outpatient setting so patients can perform normal daily tasks without suffering nausea, insomnia, and other opioid withdrawal symptoms. Patients who choose MAT can continue to attend counseling and aftercare while in therapy to learn the skills needed to stay sober for life.